Een club voor liefhebbers en/of bezitters van een zeiljacht van het Oostzeejol type Midget.

![]()

A week of "England"

Midgetsong 1998

Affliction or virus

German Sands

Razzle Dazzle

"The

Passage" 2003

From

Greetsiel to..

2350 seamiles against the

clock

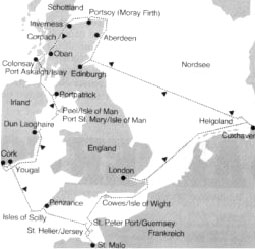

2350 Seamiles against the clock, around England, in a 20' Midget.

left the trip, on the right sailor Norbert Balzer.

Thans Wim Hart for the translation !

From: the German YACHT no 5 1979

In the past, faithful "Spitsgatter" (Double-ender) readers will have made aquaintance with Norbert Balzer, who made a journey of 1700 seamiles in his Midget "Mollymauk", and reported this under the title "1700 Miles in a Nutshell" (Spitsgatter 50). On his trip from Helgoland via Holland, England to Norway, it had bothered him that he had to pass up on Scotland. A year later he made good on this neglect, and notched things up a bit by circumnavigating England. Herewith is his chronicle.

Ireland, the Green Isle, was to be the target of a new journey with my 5,85 m l.o.a. double-ended Midget "Mollymauk". Initially I wanted to head for Scotland, because the previous year, during my Norway trip, I had to abolish the planned sidetrip to this Northern part of the United Kingdom. This time I wanted to make up for this omission, there was also an additional motivation; again the Helgoland-Edinburgh race was included in the Northsea-week programme. When participation with my "little boat" was denied, I wanted to sail along anyway, as non-competitor, faithful to the principle; "Belonging is Most Important". In a hunderd days we would sail around England.

|

|

|

The question of who would join me, gave me some headaches, because who would have this much time? The problem soon solved itself. Dirk, an enthusiastic ham operator, until recently deck hand on a minesweeper and now student, waiting for a placement, eagerly signed on. He would have preferred to make Mollyhauk into a full-fledged shortwave radiostation. Only by pointing out the limited power capacity, did I manage to change his plans. A friend of mine came along as third crew member for the Helgoland-Edinburgh leg.

We provisioned the boat for a hunded days and that was it. A couple of hours after the racing fleet had left the harbour direction Edinburgh, we head out to sea with the same goal. The mood onboard is excellent. Immediately we initiate the usual four hour watch system, which has the advantage that, with a crew of three, each can have an eight hour sleep. Only not the skipper, since the navigation takes a considerable amount of time. Before the start we got an up-to-date weather bulletin, but instead of SW 4 we usually have N to NE 2, with calms in between, which we use to play a game of cards.

For navigation we use the trusted formula: radio beacon, sounding , course and distance made good, giving us our approximate location. The evidence: after five days out of sight of land the Island of May is dead ahead and we enter the Firth of Forth. With windless weather, we motor the last twentyfive miles to Granton, where we arrive at seven in the moring, on the proverbial last fumes in the tank. Here in Granton we meet up again with our racing friends. Two days later the last German sailors have also departed for the return trip to Helgoland. Dirk and I are feeling somewhat lonesome in this desolate and dreary harbour, and we are glad to carry on. We are in agreement on the destination of our trip: the Westcoast of Scotland, but the passage there offers two possibilities. Around the north of Scotland through the Pentland Firth, or through the Caladonia Canal. Deciding on the Pentland Firth would mean that at the end of the journey we will have rounded all of the British Isles, something that'll surely look better on the charts. Deciding on the Caladonia Canal, however, would mean a shorter route, so a considerable time advantage, attractive scenery and greater security. The latter argument finally settles it. Dirk, his head full of sailing adventures, initially is not too happy with my decision to take the "boring" Caladonia Canal.

So I read him the appropriate passages from the Pilot, which speak of unexpectedly high swells, tidal rips of ten knots and dangerous sideswipes because of the currents. That finally convinces him.

So our next target is Inverness at the entrance of the Caladonia Canal. The course takes us along the Scottish eastcoast to Moray Firth. In Aberdeen we tie up for eight hours and are charged the rip-off fee for an entire week. After this experience I can advise every sailor to sail a big circle around Aberdeen. Also in Scotland sailors appear to be ripped off these days. Along the small port of Portsoy on the southside of the Moray Frith we reach Cromarthy Frith. Here we are being met, and accompanied for some time by a pod of dolphins, a beautiful sight, which according to the local population of Cromarthy will often repeat itself . Finally we reach Inverness. Except for the impressive castle, the city offers nothing momentous and we are glad to reach the canal. Having concluded the required formalities, the first of the twentynine locks is closed behind us.

With its sixty seamiles, the Caladonia Canal is the shortest connection between the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The canal, constructed right through Scotland, runs through three large lakes, of which Loch Ness is the largest and best known. Only on the canal sections sailing is not allowed. As far as scenerey goes, the Caladonia Canal is well worth it. Green slopes are intertwined with forests and snowcapped mountain tops. Achorages are plentyful in the Lochs. Cruising here is a tranquil endeavour. One does not have to be apprehensive of the locks. The lock keepers are extremely cooperative. The locks themselves, one could characterize as antiquated. Not only because they are operated by hand, sometimes after several attempts the gates close with a grinding and a halting, so that every time one is glad that yet another one has functioned.

After three days in Corpach, the end of the canal is reached. Here we are required to pay, our trip from the east- to the westcoast has cost us nineteen pounds. In view of the time saved, a reasonable amount. Here on the westcoast the climate is considerably more inclement. The North Atlantic and the tempestuous Irish Sea are in immediate proximity. The weather still holds, at least till just before Oban. Innocently we proceed under full sails, when in the southeast the sky suddenly blackens. Minutes later we are caught by a heavy downpour, reducing visibility to zero, forcing us to heave-to, a taste of sailing pleasures to come. From now on the weather remains unreliable and cool. Oban is the most important harbour in this area but totally unsuitable for yachts. It is impossible to keep track of the many times we had to move from one corner of the harbour to another, during our three days' stay, to make room for commercial vessels.

Three miles southeast of Oban, with the help of the Pilot, we find a well protected anchorage among rocks and overgrown islands at the southside of the Firth of Lorne. Here is Scotland the way we had expected it to be; darkgreen hillsides and rocky islands. Everything is untouched, somewhat ominous and of a strange rugged beauty that makes you forget the true nature of this area. One look at the charts reveals why: everywhere unpredictable currents, ripe tides, dangerous shallows and poor anchorages: all the things that would bring any sailor into a state of alarm. Here a harbour is seldom well protected, leave alone an anchorage, that is if there is one at all. It is not advised to visit islands that do not have dockage. The bottom is rocky and heavily overgrown with weeds, which frustrate any attempt at anchoring. As a warning we discover bewteen two islands the wreck of a fishing cutter.

The weather deteriorates. We want to reach the Irish Sea as quickly as possible, before we get stuck here on the Scottish west coast. I choose a route through the hardly one mile wide Sound of Islay between the islands of Islay and Jura and after that through the North Channel between Mull of Kintyre and Northern Ireland. Destination is Port-Patrick on the peninsula Galloway. The infamous North Channel does not let its reputation down. The wind is blowing 7 to 8 Bf. from the northwest and we are passing through the channel in record time: Seventy five miles in fifteen hours. Most of the time we are only carrying the jib. At dusk, when Port-Patrick comes into view, we are still doing five knots under bare poles. But we're not there yet. Anxiously I am searching for the the harbour entrance lights, as indicated on the chart, not a thing. Only the rocks in front of the harbour contrasting freakishly and threatningly against the clear night sky. Did we pass the harbour entrance? A small opening appears between the rocks, grows larger and behind it the lights of the coast. With the motor on we stear towards it, while a brisk current squarely opposes our course; it really is the harbour entrance. Later on we are told that the lighthouse keeper had gone home and that was why the light was doused. Foreign countries, foreign customs.

Thirty miles to the south in the middle of the Irish Sea lies the Isle of Man, our next target. Two harbours we intend to visit on this island, Peel on the north coast, with a harbour dry at low tide and Port St Mary on the soutside, also falling dry. The course from Peel to Port St.Mary leads along the high coast of Man, past the Calf of Man a small outcrop of rocks and Chicken Rock with a lighthouse as point of recognition. Dangers in this area are the strong rip tides and the forceful cross currents which can present the unsuspecting sailor with great problems. In the Port of St.Mary we enjoy a friendly reception, we are the first German yacht in the harbour since two years. Ireland is now reasonably within reach.

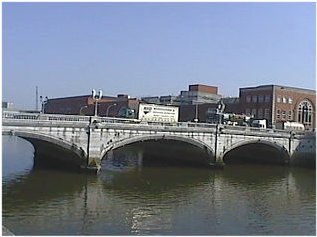

Patrick Bridge, Cork.

From Port St.Mary we set out on an approximate seventy mile course for Dun Laoghaire, not far from Dublin. Dun Loaghaire has excellent harbour facilities, buoys for yachts, a protected yachtbasin and a ritzy yachtclub. Now another 150 miles to Cork, our final destination. We decide to do it in one stretch. With a favourable wind the Irish eastcoast swiftly draws past us. There appears to be truth is the saying that journeys on the North Sea, Irish Sea and the English Channel should not be taken clock-, but especially counter-clock wise. With the bad experiences of my clock-wise Norway trip in mind, I have planned this route the other way around and was promptly rewarded with mostly beam and following winds.

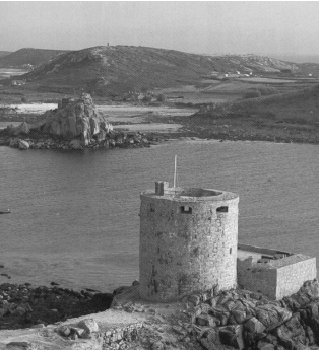

After thirty six hours we have already 150 miles behind our stern. We are the guests of the Royal Yacht Club of Cork, founded in 1720, oldest yachtclub in the world and are assigned a mooring for the next three weeks. One blow on the horn will bring the clubferry alongside, no charge. Students are maintaining the ship to shore traffic and are keeping an eye on the boat. In a rented campervan I go on an exploration trip, while Dirk goes wandering through Ireland. When after two weeks we are united again on board, we are looking forward to a new height in our summercruise. We are setting sail for the Scilly Islands. Because playing the part of landlubbers for the past fourteen days has made us a little unaccustomed to life at sea, we firtst put in at nearby Yougal, in order to definitely set out for the Scillies the next day. The piece of Altantic Ocean we just touch on that course, is showing itself from its friendlier side. Actually too friendly we find, because we are being plagued by calms. The Scillies constitute a group of forty eight islands. The five largest are inhabited. The first point of call is New Grimsby Habour, where one should not anticipate a true harbour, but an unbuoyed, snakelike fjord between the islands Tresco and Bryher. If you're lucky, with high tide, you can procede directly across the neighbouring Tresco shallows to Hughtown of St Mary, the most important harbour of the Scillies. At low tide, one anchors safely at the New Grimsby Harbour. The Scillies are ideal for those who like to explore. Each of the five larger islands has its own characteristic. Tresco has tropical vegetation, Bryher rather sparse and rocky, St Mary's the centre of tourisme, St Martins is flat and sandy, St Agnes has impressive coast formations. The island Gugh is attractive because of its loneliness and and everchanging landscape. This island is connected with St.Agnes with a sandbar that dries at low tide. We spend five days on the Scillies. Then we depart for Penzance on the Cornwall coast. From there we procede to the Channel Islands.

Cromwell’s Castle on the island Tresco

It takes us thirty hours to reach Guernsey. We tie up in the harbour of St.Peter Port, where we are received by an excellent organisation. Even now, in the middle of the night customs officers and harbourmaster, in rubberboats meet up with every entering yacht and accompany it from the harbour entrance to a temporary mooring. In the morning, or rather at high tide, every skipper tries to get his boat into the tide-free inner harbour, because here the difference between high and low tide amounts to nine meter. The traffic jam is considerable. Narrow strips of water barely divide the rows of tightly packed boats.

|

|

|

As we are in the neighbourhood anyway, we want to take a sidetrip to St.Malo. Because of bad weather we are forced to make an intermediate stop on Jersey. The harbour of St.Helier is "artificial" without any athmosphere. It is far out of town at the edge of an industrial complex. Finally we reach St.Malo. Before one reaches the tide free harbour a lock has to be passed. In the harbour we find the same conditions as in Guernsey. This area is within the reach of many countries: Irish, English, Belgian, Dutch and French are the main group of nationalities. For the German yachts this area is too far. In any case, German flags are seen only sporadically. In St.Malo happens what I had secretly feared all along. The motor gives up the ghost and cannot be repaired on board. In one way or another we are relieved. While ususally the motor has to be thought of with considerartion, this is now eliminated. Manouvering now has to be done only under sail. This not only creates more enjoyment and diversity, but also an additional sense of accomplishment. This way one uses also a little more creativity than with the old motto;"Sails down, Motor on". When we cast off at St.Malo, the lock keeper beckons from his glass booth in panic, because we want to sail through the lock ! But we turn and accept a tow from a motoryacht.

Then we set course for Wight. With an increasing SW wind and dimishing visibility we quickly pass the west side of Jersey to continue between Jersey and Sark and sail towards Alderney. Navigation in this area is not difficult, there are enough points of reference, lights and radiobeacons. What can be uncomfortable, however, are the many sneaky currents. The charts are full of warnings of confused currents and breaking seas. Especiall the "Race of Alderney" between Alderney and Cap de la Hague is notorious. With this weather and reduced visibility I find this passage too dangerous and decide to make a detour by going between the Casquet Islands and Guerney. Next I set course to the Needles Channel, the westerly entrance to the Solent, separating the Isle of Wight from the English mainland. We reach the approach to the Needles Channel at night. Strong currents are running in an east- west direction in front of the south coast of Wight and , when traversing this current, the in or out running water from the Solent, even in moderate winds, causes breaking seas on the adjacent shallows. As soon as we are in the Solent the seas become quiet. As we had calculated in advance, the current is with us and soon Cowes appears straight ahead. Now we have to show that we can also operate without a motor. Entering goes well, and if we also perform a flawless docking maneuvre, we only owe the motor a condescending smile. In Cowes the races of the famous Cowes-week are just starting. The entire place is dedicated to sailing. We don't allow ourselves much time, because London, our last main goal before our journey home, awaits us.

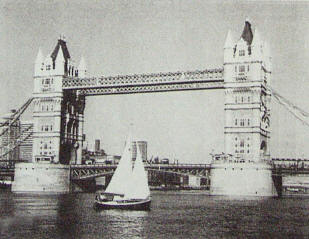

The Mollymauk and the Tower Bridge.

At an extremely quick pace we pass the English south coast, along the white cliffs to Beachy Head. Because of the strong favourable current we are regularly doing eight knots over the bottom. The following night we are sailing through the Straight of Dover and in the morning we reach the lightship in the Thames estuary. The wind has turned westerly so we are forced to tack upstream. We take the route via the lightship East Goodwin and the Princess Channel, direction of the main shipschannel. In order to wait for a favourable current we have to anchor twice and then we have made it: the "Mollymauk" lies straight across from the Towerbridge, in front of the lock to the yachtharbour St.Katherine. We have the satisfied feeling of having achieved something and have earned London. Four days we explore the city and then again it's "Hoist the Sails". Nothing can hold us back, we want to sail non-stop to Cuxhaven.

Forty eight hours later we have reached the lightship Texel. In the final leg we pass the East Frisian Islands and in the morning the mouth of the Elbe lies before us. As we pass the "Kogelbaken", the characteristic building of Cuxhaven, we have done 2350 seamiles and have visited twenty three harbours in four countries.

Anticipation, planning ahead and taking no chances is the formula of success for big journies in small boats.

Ship and crew have returned safely, what else does one want?